How Many Idiots Will Plug Random USB Drives into Their Computer?

Ashley Allen / 9 years ago

You’d have to be stupid to pick up a random USB drive off the ground and connect it into your PC, right? If the answer is yes (which it is), then there’s a whole lot of dunces out there wilfully putting their computer security at risk. A new study by researchers from the University of Illinois, the University of Michigan, and Google has revealed that at least half of people will pick up a foreign USD drive they find and use it.

As told in a paper titled “Users Really Do Plug in USB Drives They Find” [PDF], the researchers investigated “the anecdotal belief that end users will pick up and plug in USB flash drives they find by completing a controlled experiment in which we drop 297 flash drives on a large university campus.” The results found “that the attack is effective with an estimated success rate of 45–98% and expeditious with the first drive connected in less than six minutes.”

297 test USB drives were dropped at random locations around the University of Illinois’ Urbana Champaign campus. 98% of these drives were moved from their drop location, with 48% plugging them into their computers and opening the files stored on it.

“It’s easy to laugh at these attacks, but the scary thing is that they work—and that’s something that needs to be addressed,” lead researcher Matt Tischer told Vice Motherboard.

68% of those who used the USB drives admitted that they took no precautions when using the USB device when questioned afterwards.

“I trust my macbook to be a good defense against viruses,” said one of the USB users, while another confessed, “I sacrificed a university computer.”

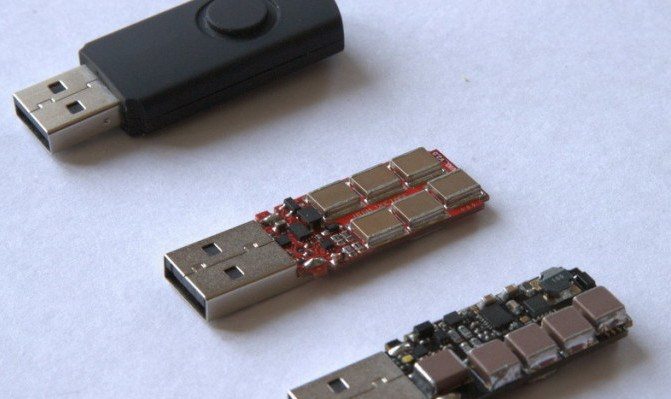

Viruses should be the least people’s worries: last year, we reported on the Killer USBs, versions 1.0 and 2.0, a pair of flash drives designed to fry any computer into which it is plugged.

“There are no easy solutions to these problems, but they will certainly extend beyond simply the technical to include a deeper understanding of the social, behavioral, and economic factors that affect human behavior,” Tischer added. “There is a difference between warning users that a particular action is dangerous and convincing them to actually avoid it. We need to close that gap.”